Photography lecturer shoots editorial commission for The New York Times

11 February 2026

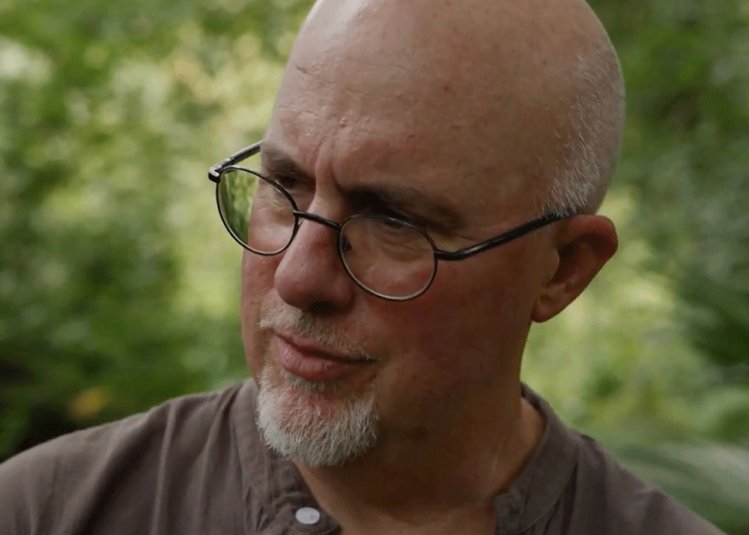

BA(Hons) Photography (Online) lecturer, Celine Marchbank, has recently captured the 96-year-old Ghanaian photographer, James Barnor, as part of an editorial commission for The New York Times.

The latest New York Times Magazine Artist Questionnaire article is a piece that reflects on James Barnor’s longstanding career in photography, meditating on the studio portraiture, photojournalism, editorial commissions and social commentary of the work he took across six decades.

Having been invited by the publication to photograph the story, we caught up with Celine to learn more about the experience of photographing James Barnor in his home. In doing so, she was reminded that, in her words, “great creative lives are not always shaped by grand surroundings, but by long-term curiosity and dedication to the craft.”

Can you tell us more about what you were looking to capture in your photographs for the piece?

As this was an editorial commission, I was working under clear direction from the picture editors regarding what they wanted visually. The photographs were for The New York Times Magazine Artist Questionnaire feature, where they interview a high-profile artist and photograph them in their creative space, usually their own studio. There were strict style guidelines to follow, while still making sure the images felt recognisably like my work, which is why they commissioned me.

I really enjoy editorial commissions for this reason: you’re given tight parameters and limited time, and you’re expected to produce your strongest images within those constraints. It’s challenging but enjoyable.

The picture editors were very open about the limitations of this particular shoot. James Barnor is 96 years old and lives in a retirement home, in a small and rather cluttered apartment with limited natural light. His photographic archive is stored in a cupboard in the communal hallway. This wasn’t going to be the typical sunlit, open-plan New York studio shoot; it required a different, more sensitive approach. I also needed to work at a pace that allowed James time to rest between shots (as well as the time limitations I was working with around childcare).

That said, I’ve photographed in many people’s homes over the years, so I felt confident I could achieve what they needed.

How did your collaboration with The New York Times first come about?

They contacted me directly by email to commission the work. I assume they had seen my photography beforehand. I’m known for natural, intimate portraits and details made in people’s homes - perhaps I’m starting a new genre!

I’ve also been working with several American curators over the past two years who have acquired my work for their institutions, so it’s possible I was recommended. I’ve also previously had work published in The New Yorker, which may have contributed. You never really know, perhaps I should have asked.

What did it mean to you to photograph James Barnor?

I’ve known James Barnor’s work since visiting his first major European retrospective at the Serpentine Gallery in London in 2021. It’s a beautiful archive. Photographing another photographer is always a special experience: they understand what you’re trying to do, tend to be relaxed in front of the camera and thankfully don’t ask the usual questions people often ask during a shoot.

We spent an enjoyable few hours together talking about photography, politics and our histories, and discovered some unexpected overlaps. My grandfather was a journalist, and we realised he and James may have been present at some of the same events, specifically the Muhammad Ali boxing matches.

Is there anything else you would like to share about this experience?

Photographing artists within their lived environments feels important to me because it provides context and reflects the practical realities of artistic practice. Working with James Barnor in such an intimate setting was a reminder that great creative lives are not always shaped by grand surroundings, but by long-term curiosity and dedication to the craft. Seeing him share his life’s archive from a cupboard in the shared corridor was particularly poignant, highlighting both the quiet reality of an artist in later life and the lasting legacy that creative work leaves for future generations.