One take filming: what shows like Adolescence tell us about acting

21 October 2025

This article was originally written by Head of Theatre Arts, Dr Trevor Rawlins, on Substack. Trevor uses Substack to share his reflections on his own academic and professional activities and how they relate to the craft of acting. He also brings forth wider discussions on acting, actors and storytelling.

____

In the second episode of The Studio currently being released on Apple TV, Seth Meyers’ studio boss waxes lyrical about the “oner” in a film his studio is currently shooting. That episode is, itself, called “The Oner” and is also actually shot as a oner - a one take shot from start to finish. Adolescence on Netflix is a four-part series where each episode is a single take, from the same team who made the single take feature film Boiling Point in 2021.

I delayed watching Adolescence until I had completed the production of Boudica by Tristan Bernays that I have been working on at Falmouth University, UK, so I only caught up with it at the weekend. It’s been deservedly getting a lot of coverage for its subject matter and for being one take episodes. I think there may be some innovative things going on with the acting and storytelling in response to demands of one take filming.

I have been in the production bunker so I may well be unaware of what others are saying about Adolescence. I have also only watched it once at this point. I may change my mind about what I am about to say here and I may be making some incorrect assumptions.

There are films that are genuinely shot in one take, Boiling Point being an example. There are films, like Sam Mendes 1917, that are made to appear as one take but are actually a series of much shorter one take sequences. That is the kind of scene that Seth Meyers’ character was speaking about in The Studio. Both are coherent choices. I am not aware of a TV series being shot as a series of one take films, each around 60 minutes long, until Adolescence. For me at least, Adolescence is therefore a new experience.

Reports vary for how Adolescence was made but it seems that each episode was filmed multiple times in one take. The most reliable report I can find says that each episode had five days of shooting time, with two complete runs of the episode filmed each day. Meaning ten complete one take versions of the episode. In the end one complete take was selected for broadcast.

One of many things that is important about this way of working is what it means for the nature of rehearsal. I have written about the changing place of rehearsal a lot over the last 15 years or so because it really alters the way actors get ready to perform. What I have been doing as a teacher of acting has been to try to re-imagine traditional techniques and approaches that assume lengthy rehearsal as has been the case in theatre, for the contemporary working life of the actor working in TV and film where there is minimal or no rehearsal. Actors today work in isolation much more than they used to, even more in very recent years when so much of the auditioning process now happens via self-tape. The actor works largely alone and sends the self-tape file over the internet rather than even meeting a casting director - at least until later in the casting process. The filming process is similar, with actors preparing at home and coming to set to film, with rehearsal merely being the thing that happens right before the scene is shot. The notion of a lengthy and in depth exploration of the text as a group activity building over weeks towards a final performance has become rarely, if ever, a part of film and TV.

But that flips back to the theatre model when a whole piece is being shot in one take. If anything the rehearsal is even more extensive as it can involve supporting artists as well as actors and a whole film crew who all need to be able to perform every action exactly on cue and with precision for the length of the whole piece. In the case of Adolescence that is about an hour each time. I don’t want to spoil anything for anyone, but episode 2 is probably the most extreme example of the sheer amount of rehearsal, organisation and co-ordination that needs to happen in order to achieve this. One mistake by anyone of the hundreds of people involved could mean the whole take is wasted. The chances of that messing up schedules and therefore making the film blow its budget is just one of the reasons that shooting films in short bursts became the standard very fast, and remains so.

One of the main differences between acting for the theatre and for the camera has always been the repetition involved. To slightly over-simplify, on camera the actor only needs to get it “right” once - or at least only a few times. And right could mean producing some subtly different versions over a number of takes to give an editor options later on. In the theatre, the actor needs to be able to repeat the whole performance multiple times - typical eight times a week for the length of the run in the UK. Acting for the camera therefore tends to require a perhaps greater emphasis on spontaneity and, with the exception of considerations of continuity, less emphasis on consistency of repetition. Theatre typically would be the opposite. One take shooting requires both. This is one of the main reasons what is happening with shows like Adolescence could be revolutionary for acting.

One of many things that is striking about Adolescence is the quality of the acting. That has to be, at least in part, because of the rehearsal time. Rather than doing all their preparation alone and then having quick rehearsals right before shooting, rehearsals have happened well before shoot days and the actors have had time to prepare together. I imagine choices about blocking, camera positions, sound recording and even exact locations of scenes have also been made at least partially collaboratively during those rehearsals so that everyone involved has a full understanding of what is happening during filming. Often as an actor you feel like someone just pushes you on set, barks a bunch of instructions at you and then you hear “action”. The skill is in making it work at all, not in producing extraordinary choices. The realities of one take filming means the rehearsal time has to be there and those more considered choices can be made. Paradoxically, we may be seeing a resurgence of, to borrow the American actor and teacher Uta Hagen’s book title, respect for acting.

One take also changes the way the film is written. Each episode of Adolescence has to be in real time. Real time means that what might not be included in a conventional film has to be and anything that cannot be part of a real time hour cannot be. The exact occasion of the four one hour episodes within the story have to be carefully selected and any moments in that real time hour that may not seem the most dramatically useful have to be made so. Episode four has some great examples of using the moments that may not otherwise have been included. For reasons of the plot, the family at the centre of the story need to make a trip from home to a DIY store and back again having done some shopping, in their van. That is a real journey so the scenes that happen in the van have to match the exact time that journey takes. If the film wasn’t being shot as one take it seems highly unlikely these scenes would be in the film. If they were, they would not be at the full length that they are in Adolescence. As they are, we see the private moments of that family in ways we otherwise would not. The actors get to play out the character interaction much more than they typically would.

Watching these scenes and others put me in mind of social realist work by filmmakers like Ken Loach, Mike Leigh and Andrea Arnold. Those filmmakers all use forms of improvisation somewhere in their process. Often the actors look like they are not really acting at all. The one take process, somewhat paradoxically because it is as fully rehearsed as anything is ever likely to be, comes over in a similar way. I think partly that is the way it has been created through extensive rehearsal and partly in the way it has had to be written to include some the moments a writer would usually leave out. To paraphrase the Russian playwright Anton Chekhov, who said the drama was real life with the boring bits taken out, one take is drama with some of the boring bits left in. The “real” in real time therefore adding a layer of realism to what ends up on film.

But real time also means that there can and must be space for improvisation. There is a moment in episode three of Adolescence when a character yawns. The actors in that scene, Owen Cooper and Erin Doherty, have discussed that moment so we know it was no rehearsed. Owen yawned simply because, as he tells it, he was tired. Erin then improvised a response that was not scripted or rehearsed. As it happens, the camera was on Owen at that point, so not only do we see the yawn, we also see Owen’s in the moment reaction to the improvised line. It is a real time moment. It is perfect, largely because both actors are alive to the moment and remain within the structure of the scene. In an interview, Meryl Streep described this kind of event as the “tangent energy” - the thing that comes out of the blue, alters the scene creating something new and unique that could not have been planned.

There are so many things that Adolescence raises that I could just keep writing. The last thing I want to mention here, for now at least, is the way the four episode structure works in relation to the storytelling and the character through-line from the actor’s perspective. In a classic story structure, there is a protagonist. In a classic play following Aristotle’s model, the protagonist would be the main character who will be changed in some way by the events of the play. That character will likely be in most, if not all, scenes of the play. Broadly that is still the basic structural model for drama and comedy in a European view of structure - much of that is rightly challenged today by ideas of decolonisation. I need some more time to think about this, but it occurred to me when watching Adolescence for the first time that this structure is being played with. I may be wrong, but on one viewing it seems to me that no one character is featured heavily in more that two episodes. Some characters do appear in a third but only in a brief way. I don’t think any character is in all four episodes.

Owen Cooper’s character Jamie is the protagonist in terms of the action, because it is his actions that drive the whole story. Stephen Graham’s character Eddie drives episode four and parts of episode one. Ashley Walters’ character Luke drives parts of episode one (he is the first character we see) and all of episode two. Episode 3 is largely a two-hander between Cooper’s Jamie and Erin Doherty’s Briony. I don’t want to go into too much detail because I don’t want to spoil it for anyone who hasn’t yet seen it.

Adolescence is rightly getting a lot of attention as a drama that articulates some important issues and has people talking about those issues. It is also getting a lot of attention for the quality of the acting and the storytelling and I think there is a lot more to be unpacked about what the show tells us about both in today’s world.

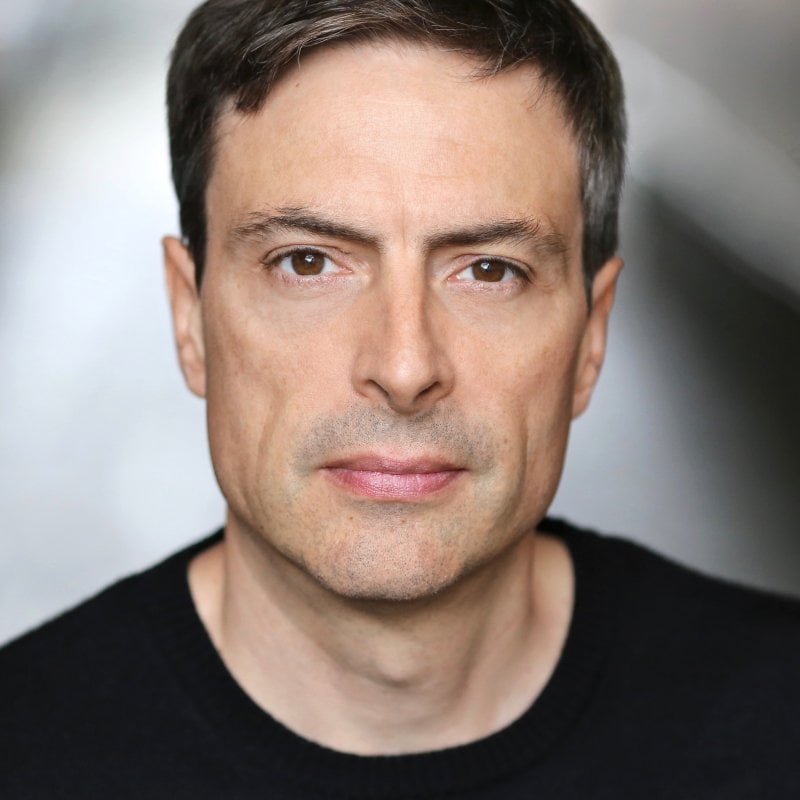

About Dr Trevor Rawlins

Trevor trained as an actor at East 15 Acting School. Before joining Falmouth, he was Head of Acting at Guildford School of Acting (GSA) at the University of Surrey for eight years. Prior to that, he worked as an actor and director in theatre, film, tv and radio.

He has taught acting since the late 1990s. He has had a long association with Shakespeare's Globe Education Department, where he was Director of postgraduate courses. He has taught and directed productions at a number of drama schools in the UK including East 15, ALRA, Italia Conti, Drama Centre, Royal Conservatoire (Scotland) and Birmingham School of Acting.

He is a Senior Fellow of the Higher Education Academy.

You can continue reading about Trevor's professional experiences in his Substack post, Talking Acting.

Find out more about Dr Trevor Rawlins and our Academy of Music & Theatre Arts.