Falmouth filmmakers on folk horror, community and the Cornish landscape

28 October 2025

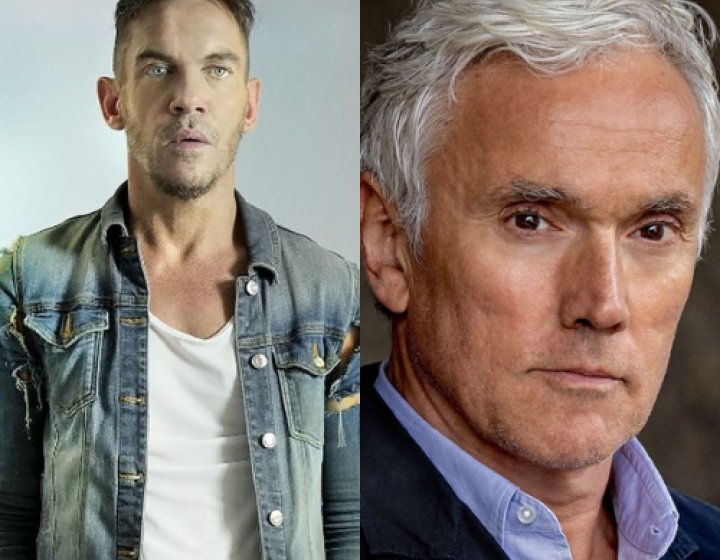

A still from The Severed Sun. Credit Steve Tanner

Horror films have an enduring popularity amongst film fans, delivering adrenaline rushes and raw human storytelling across a wide cinematic spectrum. For filmmakers looking for fertile ground to craft these stories, Cornwall’s culture, history and landscape offers inspiration in abundance.

From BAFTA-winner and Falmouth’s Distinguished Professor of Film Practice Mark Jenkin’s lauded film Enys Men to lecturer Dean Puckett’s recently released debut The Severed Sun, an array of exciting folk horror films have emerged from Cornwall over the past few years.

We chatted to Dr Kingsley Marshall, Head of the School of Film & Television and writer/director Dean Puckett, to learn more about folk horror and why Cornwall is such a powerful place to make films.

Firstly, what got you both into horror films?

KM: I read a lot of horror as a kid, and in the 1980s at my school a group of friends circulated contraband in the form of VHS tapes containing copies of US and European horror movies. Those tapes brought the kind of stuff I’d been reading – books by Stephen King and Elizabeth Engstrom – to life. I’d seen a few mainstream horror films on TV, but that schoolyard swap shop was my introduction to directors including Tobe Hooper (The Texas Chainsaw Massacre) and Dario Argento (Suspiria), as well as a stack of the so-called ‘video nasties’, including Maniac, the Cannibal series, and The Evil Dead.

Those films made a big impression on me, in part as they had characters only a little older than I was at the time, but more so in how they revealed a whole new universe. My friends and I would talk about them in hushed tones, trading stories about how they were made gleaned from magazines like Fangoria. There’s a great film that conjured up that whole era by Prano Bailey-Bond called Censor, which came out a couple of years ago. To be involved in making horror movies now and be adding to that canon of films as a producer and writer feels like a real privilege.

DP: I watched the original broadcast of Ghostwatch when I was ten years old, and then A Nightmare on Elm Street the same year. The two things fused together in my mind to create a lot of nightmares, but also a morbid fascination with horror movies; I liked how they made me feel. I also used to glance up in awe at the deranged VHS covers in the video shop and feel myself being drawn toward them like a lemming staring at the edge of a cliff.

What distinguishes folk horror as a subsect of the broader genre, and why do you think it’s popular with audiences around the world?

KM: The ‘folk’ element comes from the people within often rural communities and their relationships with the landscape and those around them, while the ‘horror’ is born of the situation they find themselves, often drawing from established folklore or superstitions. I love the reality of these settings; thinking about characters as ‘people in a community’ or world, and how organised hierarchies can both create and connect those within the communities or fester hatred or vengeance.

Eeriness exists everywhere, if you know where to look. In US movies, folk horror is often about the clash between the modern and the arcane, the ordinary and the uncanny. These themes are universal and familiar to us all, after all, we’re all characters living in a landscape, and every place comes with a history and is shaped by what’s happened there.

DP: I think we are living in really strange times when it comes to how we perceive our neighbours, friends, and fellow citizens. Depending on whether they have read a dodgy Facebook post or not, the people around us can come out with some very unexpected and strange algorithm-driven opinions or regressive nonsense. This sense of unease and post-Brexit, post-COVID, late-capitalist malaise has seen a rise in populism and a simultaneous rise in folk horror. The evil that people will do to one another is a central idea in folk horror, so it's no surprise to me that it is at its most popular when we are most divided.

Falmouth's Sound/Image Cinema Lab (S/ICL) has supported a range of exciting folk horror films over the past few years; from the award-winning short film Backwoods to Mark Jenkin’s Enys Men and now your film Dean, The Severed Sun. Why is folk horror a big focus for S/ICL?

KM: As a production partner, the Sound/Image Cinema Lab has been involved in feature film production since 2009, and horror is certainly not everything we’ve done – in that we’ve worked alongside filmmakers making all kinds of stories – a road movie, a stoner comedy and a musical, a 1960s love story wrapped around jazz music, and a coming-of-age story, as well as some great documentaries, major label music videos and a huge number of short films.

That said, our most recent films including Dean's The Severed Sun and Mark Jenkin’s Enys Men and forthcoming Rose of Nevada, all represent the strange times we live in, and certainly – like most horror – reflect our society. On its release, Enys Men was described by critics as representing “a new weird”. It represented Cornwall’s rich history and landscape but also a sense of the confused nature of identity, memory, and time. The Severed Sun is a story about people turning on one of their own, of persecution and sacrifice, about a lack of kindness. It feels like we can't move in the world without bumping up against these themes right now.

Dean, how does it feel to have released your first feature-length film? And what does the experience of directing a folk horror film in Cornwall feel like?

DP: Making my first feature has been a huge learning curve. It feels like it took making a feature to actually learn how to make one—which sounds obvious, but the British film industry has a habit of fetishising the first feature, as if artists need to arrive fully formed. I think of it more as a process.

I’m really proud of this film, but I genuinely hope I get the chance to apply everything I’ve learned during this process and make another one! Cornwall is just so rich with folklore, myth, and atmosphere—Bodmin was the perfect place for this story. I love shooting in Cornwall, living in Cornwall and being inspired by the landscape and people.

Kingsley, as the co-founder of production company Myskatonic, what piques your interest in new folk horror film ideas?

KM: We describe Myskatonic as a company that uses the horror genre – the eerie and the supernatural – as a Trojan horse to communicate political ideas. Our slate of films and TV series reflect our view of the world, and we use genre to carry across to a global audience our own thoughts about the issues that we care about – grief and loss, climate change, the migration of people, and the impact of technology on our lives.

From the landscape to the history and people, why do you think Cornwall is a unique well of inspiration for folk horror stories?

KM: Cornwall as a place where the new and the old collide, whether that’s in its language or culture, the decline of industries that extract from the earth or the sea, and watched over by ancient sites that have stood for centuries – manifested in the standing stones, settlements and burial chambers that pepper the landscape. Even the campus on which the School of Film & Television stands dates back hundreds of years, the dissolution of an ancient college here playing a part in triggering the Prayer Book Rebellion in 1549. There are stories around every corner; a rich seam of history to draw upon, and with some incredible cinematic locations.

Finally, why is Cornwall a powerful place to come and study filmmaking?

KM: Cornwall and its people are born into an independent spirit, with long connections in language and culture to the Celtic traditions of Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Brittany and beyond. We live at the edge of the UK and are bounded by the sea, and I think that plays a large part of who studies and works here with us at the University. Our students arrive at Falmouth University with a desire to find their voice and are empowered by each other and the wider team in the School of Film & Television to tell their own stories, often coupled with wanting to make a comment or instigate a change in the challenging world they see before them.

We have incredible staff, equipment, and industry-standard facilities here, and have been able to place large numbers of students onto professional projects, including three feature films in the last year or so, for well over a decade. The opportunity to gain professional credits and set experience before leaving university is a big draw for our students and certainly helps filmmakers build their confidence while they are here and take their first steps in the creative industries when they leave.