Game Art lecturer on his time in the industry and the future of games

12 August 2025

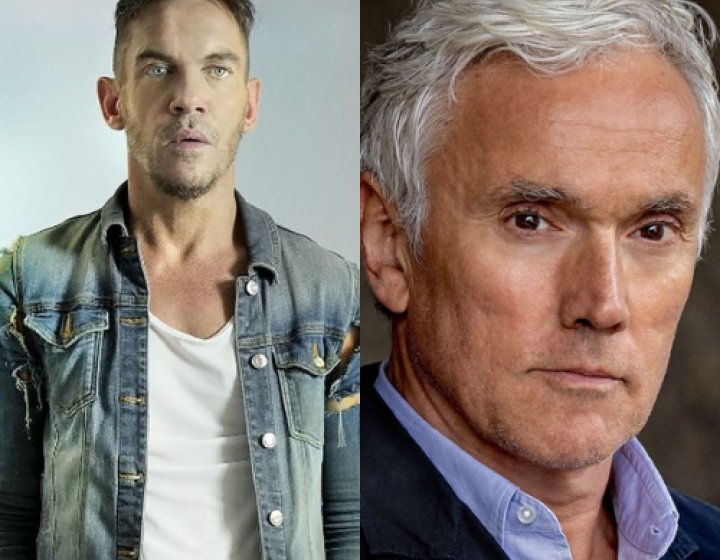

With a career that spans iconic titles like Tomb Raider: Angel of Darkness and GoldenEye 007, Associate Lecturer in Game Art Ady Smith brings decades of industry experience into the Games Academy. From his early days at development studio Rare during the UK’s golden age of games development to leading art teams at Electronic Arts (EA) and beyond, his journey reflects the evolution of the industry itself. Now, he is helping students at Falmouth develop the creative and technical skills they need to break into a fast-moving sector.

We caught up with him to hear about his time in the industry, why he moved into lecturing and his thoughts on the future of games development.

You started your career at Rare with Donkey Kong Country and went on to work on GoldenEye 007, which won a BAFTA. What were the most memorable moments or milestones from your time in the industry?

One of the standout moments was working on my first game straight after finishing my master’s at the NCCA (National Centre for Computer Animation) at Bournemouth University. Moving from eight years of education into the fast-paced world of commercial game development was a huge shift.

Donkey Kong Country marked the beginning of Rare’s golden era. The company had recently changed its name from Ultimate – Play the Game, a studio now considered part of gaming history. That game was my first professional project, and I was lucky to be part of the team that won 'Game of the Year' in 1994 for the SNES version. It was a matter of being in the right place, with the right company, at the right time.

How did the culture at Rare and EA shape your own creative approach and standards?

I spent eight years in further education after leaving school. I was a fairly average pupil. I worked hard, but my parents were once told I wouldn’t amount to much. They couldn’t have been more wrong. That comment stuck with me, and it’s one of the reasons the college and university system suited me so well.

I followed the full art and design education route. I started with a foundation course in 3D Design at Lincoln College of Art, then moved on to a BTEC HND in Product and Packaging Design, before progressing to a BA(Hons) in Industrial Design at Sheffield Polytechnic. That’s where I was introduced to CAD and CGAL programming. My interest in CAD and computer animation led me to an MA and PgDip in Computer Animation at the National Centre for Computer Animation (NCCA) at Bournemouth University. It was there that I built my industrial design and CG portfolio, which would define my career in the games industry for the next 30 years. I’m proof that the system works.

My portfolio had a strong product design focus, which naturally aligned with the environment art side of game development. In this industry, your portfolio often determines your path. That’s also how I assessed new recruits at Rare, matching their skills with the right game projects.

At Rare, I established myself as a Lead Environment Artist. But I didn’t want to stop there. I was fascinated by visual effects and began training myself to create VFX assets for our games. I effectively became the VFX department and played a key role in developing the effects for GoldenEye 007 on the Nintendo 64. At the time, effects work was usually left until the end of development, almost as an afterthought. My VFX work fed directly into my environment design, helping me add dynamic effects into the levels I was building. Everything was developed using Alias PowerAnimator.

My understanding of environment art and VFX pipelines helped me move into the role of Lead Artist. That foundation of knowledge has supported me through every game I’ve worked on since, across all the studios I’ve joined.

After decades in AAA studios, what inspired you to move into teaching and what keeps you passionate about it?

My move into teaching began during my time at Rare. I was a Senior Graphic Artist, and while Kevin Bayliss, our Art Director, focused on the development of Killer Instinct, he asked me to help train new staff. I introduced them to Alias software, assessed their strengths, and helped assign them to different production areas.

Later, when I took a role at Bell Fruit Games in the gambling sector, I had Fridays free. I used that time to support the games development students at Hull College on their BTEC HND course. That was my first proper experience as a guest lecturer. I helped with coursework and portfolio reviews, which gave me a real taste for teaching and mentoring.

What do you see as the key skills students need now that didn’t exist when you entered the games industry?

Back then, courses were far more general. Studios often saw them as irrelevant, because they followed educational frameworks rather than industry needs. A lot of teaching was based on film, TV or music production, not on games.

This needed to change, and it took around a decade for industry professionals to move into education and help reshape it. It’s vital that universities and colleges work closely with studios to make sure graduates are genuinely ready for work. Courses must be updated regularly, and that means government and industry support is crucial.

The games industry is evolving fast, especially with AI and real-time engines. What do you think the future looks like for game artists?

The industry is going through another wave of technological change. Hardware and software are advancing rapidly, and quantum computing could bring another major shift in the not-too-distant future.

AI is already here and will affect everyone working in games. This is similar to the time when digital tools started replacing traditional art and animation techniques. That shift didn’t eliminate artists. Instead, it opened new jobs and created fresh specialisms.

AI will do the same. It will speed up production pipelines and introduce new workflows, but artists and designers will still be essential. AI is only as effective as the data it is trained on. It cannot fully replace human intuition, emotion or our understanding of ergonomics and user experience. Creative professionals will still be needed to fine-tune and shape outputs with an artistic eye.

After working on so many genres and platforms, what do you personally enjoy playing?

I’ve always enjoyed first-person shooters like Battlefield, Apex Legends and Star Wars Battlefront. I’ve also spent time on Star Citizen and am keen to try Starfield.

One of my favourite series is Homeworld by Relic. I played every instalment and still consider it the best real-time strategy game ever made.

Aside from gaming, I also keep developing my technical art skills using Houdini by SideFX. It’s a brilliant tool for procedural workflows and VFX pipelines, which are now a growing part of game development. These are the areas I encourage students to explore, as they’re becoming increasingly important in both industry and higher education.